The time the Otago Tramping Club freed the Milford track.

In the swinging sixties, New Zealand's Milford Track was the stuff of legends, a velvet rope separating the privileged from the wild beauty within Fiordland National Park. A tour there meant booking an exclusive spot on a Tourism Hotel Corporation (THC) guided journey, and access was about as tight as a rockstar's guest list.

But then, in April 1965, a band of intrepid adventurers from the Otago Tramping Club hatched a bold plan. They aimed to crack open the doors of this exclusive hideaway and grant access to the masses. Their rallying cry? Freedom for the Milford Track!

Their plan was a two-pronged assault on the trail. One faction would ascend Hutt Creek and conquer Glade Pass, emerging behind Glade House at Lake Te Anau's head. The other party ventured to Milford, with climbing ambitions after walking to Mackinnon Pass.

Robyn Armstrong (nee Norton), one of the trailblazers, explained how the phrase 'Freedom Walk' was coined. "We borrowed inspiration from Martin Luther King's 'Freedom Marches' in America. It may seem like a loose connection, but the name resonated powerfully, much like a catchy tune."

John Armstrong and his Milford-bound team faced fierce weather that thwarted their progress. "Fiordland's rain had the last laugh, trapping us just a few hours up the track. Eventually, we had to backtrack to The Boatshed and return to Milford with our fellow adventurers. But we'd made our point!"

Otago Tramping Club members camping in the Clinton Valley in 1965.

Soon after the Otago Tramping Club's daring expedition, new huts were established along the Milford Track – Clinton, Mintaro, and Dumpling Huts. These huts remain a symbol of their bold defiance, offering facilities enjoyed by all wanderers today.

It all started in 1962, the Milford Track was strictly managed by the THC. Permission to traverse it was as rare as a unicorn sighting. Students from Auckland University found this out the hard way when they attempted to venture there.

They were promptly halted, informed they couldn't proceed, and marched away. When they sought help from the ombudsman, they were brushed off as a small group unable to challenge the mighty THC. However, groups like the Federated Mountain Clubs began to question the legality of denying freedom walkers access to a national park's land.

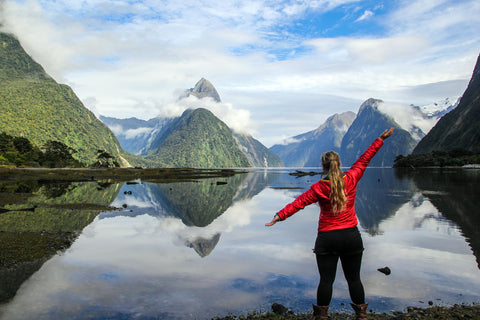

Milford sound.

The tension reached its peak in 1965 when the THC applied to lease the track and its surroundings, essentially turning it into a private playground. That's when John Armstrong and his brave comrades from the Otago Tramping Club had had enough. At just 26, Armstrong was one of the club's senior members, leading the charge that would make history.

"We didn't ask for permission," Armstrong boldly stated. "We informed the authorities of our intent. We reasoned that the track was part of the national park, and they couldn't stop us."

Fiordland National Park retaliated, claiming they couldn't proceed without THC's blessing. A THC manager in Dunedin even pounded his desk and thundered, "Permission not granted, repeat NOT GRANTED!" Yet, nothing would deter them.

On the day of departure, the National Park Authority finally granted permission, but the die had already been cast. Their journey was anything but straightforward. With limited funds to hire a boat to cross Lake Te Anau, they chose to scale Dore Pass before embarking on the official track.

Meanwhile, the rest of the group continued to Milford Sound by bus. Their plan was to hire a boat to transport them to Sandfly Point, the northern trailhead, and rendezvous with their comrades on the track. All would return to Sandfly Point, where a boat would whisk them back to their bus at Milford Sound.

But their challenges began at Milford Sound's hotel, owned by the THC. They were told they couldn't have a boat, but John Armstrong wasn't one to back down. He struck a deal with a fisherman who was willing to help but feared repercussions. With some chaos and a dash of youthful spontaneity, they secured a boat for the adventure, shelling out a mere 12 shillings and sixpence per head.

Otago Tramping Club members arrive at Sandfly Point in 1965.

The boat carried them to Sandfly Point, and they embarked on the trail, keeping a vigilant eye out for their fellow club members. However, the relentless weather, common in this corner of the world, soon unleashed its fury, swelling the rivers.

Armstrong's group reached the river crossing at the Boatshed Hut, where they faced a seemingly impassable obstacle. The Arthur River was in a tumultuous mood, too dangerous to wade. Undeterred, they ingeniously strung two climbing ropes across the river and camped on the Milford side as the water continued to rise.

As rain pummeled down overnight, the water came perilously close, stopping just 18 inches below their camp. With no plan B, they improvised, discovering a small raft hidden in the bushes and rigging it up with carabiners. The rest of the party joined them, and, using the makeshift raft, they managed to ferry most of the group across.

The next day, the rain finally ceased, and the water level dropped enough for the remaining trampers to wade across. A boat awaited them at Sandfly Point, much to everyone's relief, marking the completion of their audacious mission.

The Freedom Walk captured the nation's attention, forcing the authorities to act swiftly. John Armstrong said, "Public opinion was definitely on our side, though not quite as explosive as the '81 Springbok Tour. There were supportive editorials in numerous papers, leaving no doubt that the public stood firmly behind us."

Within weeks, the National Parks Authority and the THC reached an agreement. Freedom walking was allowed, and new huts were constructed along the trail. Undoubtedly, the agreement was a direct result of their walk, with the government choosing to stand on the side of the people.

John and Robyn Armstrong at Sandfly Point on the 125th anniversary.

Recently, on a heritage walk marking the Milford Track's 125th anniversary, John Armstrong realized the magnitude of their achievement. Guides helped them understand the broader context of their club's actions, potentially saving the Milford Track from remaining a private treasure and setting the stage for other iconic tracks like Routeburn and Tongariro.

Joining them on the heritage walk was Robyn, who had been one of the pioneer freedom walkers, leading the group that traversed the track from Dore Pass. She admitted, "At the time, I didn't grasp the magnitude of what we were doing. I was just a university freshman, seizing the chance to hike for free. But it was also an opportunity to stand up to a government department that craved complete control."